Aztec Warriors

The Aztec empire was an empire that expanded rapidly. It's not a surprise that Aztec warriors held a very important place in the culture of central Mexico. But where did the Aztec warrior come from, and what was his life like?

Training

|

The warrior was a glorified position in the society. It wouldn't be surprising to find out that your son wanted to go into the army when he grew up. As we'll see, there were also significant rewards in store for the successful soldier.

Boys in the empire would receive a good education, no matter what their prospects for a career were. Astronomy, rhetoric, poetry, history, and of course religion would all be important subjects at school. Then there would be actual training on the battlefield.

A boy became a man in society at the age of 17. For a commoner wanting to go to war, this meant starting out in the lower ranks in the army. There were servants, who basically just carried weapons and supplies. Then there was the youth in training, who had not yet captured his first prisoner. That first capture was an initiation into the world of the real Aztec warrior.

There are some great books to check out - see Aztec Warriors on Amazon.com.

Rising in the ranks

Capturing prisoners was key for a warrior to rise in the ranks of the army. To find out why capturing prisoners was so important, read about the Aztec flower war. Capturing a few prisoners was a status symbol for a young man, and rewards would follow.

There is some disagreement about exactly how high a warrior could rise in society. Would a successful Aztec warrior become a part of the "warrior nobility"? Or was that class only accessible by being born in the right family?

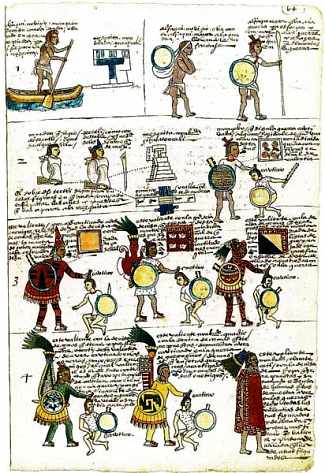

We do know that there were "societies" in the army - groups of knights that held a high rank and a high place in society. The largest (and today most well known) of these were the Jaguars (ocelomeh) and Eagles (quauhtin). Men in these societies would wear uniforms representative of these animals. See these drawings of Aztec warriors for examples.

Sometimes they would wear wood helmets with the insignia of their order. Higher classes wore bright featherwork, quilted cotton armour, mantles of blue (tlahuiztli suits). The higher the rank, the more elaborate the costume. Aztec warriors could also carry flowers, a privilege normally reserved for the nobles.

Sometimes a warrior would be given lip plug made of polished stone. The appearance of the stone would change as the soldier rose in the ranks, showing the world that he was "mighty in battle".

Rewards in Society

Someone high in the ranks had more rewards in the society at large. He could be involved in politics, for example. He had access to food normally reserved for the higher classes.

But one of the most important rewards was land. The land was tax-free, and any profit made was his to keep.

The land was awarded for life. The warrior was encouraged to have a family, and the estate could be passed down as an inheritance. Once a son had inherited the land, he could keep it or sell it.

Obviously these estates had an impact on Aztec society. Warriors and their families soon rose to a very important place in society, and became a kind of elite.

The life of Aztec warriors

The life of a warrior was often short! We don't know how short, though we know that life expectancy in the empire was around 37 years. Different periods in the life of the Aztec civilization saw different amounts of war, of course.

When word went out that a war was coming, the man had to prepare to leave his family and join the ranks. He may join a small group, or an army of several thousand.

Provisions and weapons had to be carried. Common Aztec weapons included the maquahuitl, clubs, the atlatl, and bows and arrows (tlahuitolli and mitl).

They would march between 19-32km/day (12-20mi). Of course, the Aztecs didn't ride, and sometimes the area of conflict would be quite some distance. Then the battle would begin.

More about how the Aztec warrior fit in the culture...

References: The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society by Inga Clendinnen (1985); The Aztec Image in Western Thought by Benjamin Keen; War and Society in Ancient Mesoamerica by Ross Hassig (1992); The Aztecs by Michael E. Smith (2002)